How Do Scientists Read Dna So They Know We May Have Come Close to Extinction?

Scientists Have Reconstructed the Genome of a Bird Extinct for 700 Years

The piece of work hinged on Dna from a museum specimen

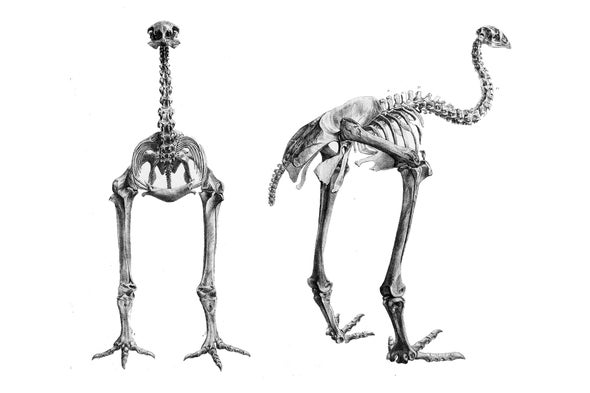

Scientists at Harvard University take assembled the get-go near complete genome of the little bush moa, a flightless bird that went extinct soon after Polynesians settled New Zealand in the late 13th century. The accomplishment moves the field of extinct genomes closer to the goal of "de-extinction"—bringing vanished species back to life past slipping the genome into the egg of a living species, "Jurassic Park"-like.

"De-extinction probability increases with every improvement in aboriginal DNA analysis," said Stewart Brand, co-founder of the nonprofit conservation group Revive and Restore, which aims to resurrect vanished species including the rider pigeon and the woolly mammoth, whose genomes have already been generally pieced together.

For the moa, whose Deoxyribonucleic acid was reconstructed from the toe bone of a museum specimen, that might require a niggling more than genetic tinkering and a lot of egg: The six-inch long, 1-pounder that emus lay might be merely the ticket.

The work on the piddling bush moa has yet to exist published in a periodical (the researchers posted a not-peer-reviewed paper on a public site), but colleagues in the small globe of extinct genomes sang its praises. Morten Erik Allentoft of the Natural History Museum of Denmark, an expert on moa DNA and other extinct genomes, chosen information technology "a significant step frontward." Beth Shapiro of the University of California, Santa Cruz, who led a 2017 study reconstructing the genome of the passenger pigeon, called it "super absurd" because it "gives united states an extinct genome on an evolutionary branch where we hadn't had any earlier."

That the assembly of an extinct genome is existence spread similar scientific samizdat is not unusual in this field. Journals demand more than from papers than "here it is," said Ben Novak, a co-author of the passenger dove study. "The number that'due south actually been done is peradventure quadruple" the four or v extinct genomes formally reported, "but the results are just sitting in people's labs."

The almost complete extinct genomes include 2 human relatives, Neanderthals and Denisovans, in addition to the woolly mammoth, and the passenger pigeon. The zebra-similar quagga was the first extinct species to have its Dna sequenced, dorsum in the genomic Rock Age of 1984, simply it's not up to modernistic standards.

Scientists are too shut to reconstructing the genomes of the dodo, the flightless bird that went extinct from Mauritius, its only home, in the tardily 1600s; and the great auk, which lived in the Due north Atlantic before dying out in the mid-19th century. Terminal calendar month, researchers in Australia unveiled the genome of the Tasmanian tiger, the last of which died in captivity in 1936.

In each case the steps were like. Scientists collect tissue samples from museum specimens: the Museums Victoria in Melbourne, Australia, had not bad Tasmanian tigers, for instance, while the Purple Ontario Museum in Toronto had a nice toe bone from the little bush-league moa. They then extract DNA. It's near e'er every bit badly fragmented as a shattered wine goblet because "Dna disuse begins inside days of death," said UCSC's Shapiro.

Luckily, that's non a problem. Today's high-throughput genome sequencers actually piece of work all-time on DNA measuring scores to hundreds of nucleotides—the iconic A's, T'due south, C's, and G'sthat comprise Deoxyribonucleic acid —long.

The tricky part is figuring out where the pieces belong on the genome: on which chromosomes and in what order. To do that, Harvard'southward Alison Cloutier and the balance of the footling bush moa team (which declined to talk well-nigh the work before its formal publication) took their 900 million nucleotides, scattered across millions of DNA pieces, and tried to match them to specific locations on the genome of the emu, a close relative of all ix moa species.

That enabled the scientists to go roughly 85 per centum of the genome in the correct identify. "The other xv percent is in their data only is hard to organize using the emu genome," said Novak. Turning tiny bits of DNA into a complete genome "has been extraordinarily hard. The fact that they could get a genome from a footling bush moa toe os is a large deal, since now nosotros might be able to apply their data to exercise other extinct bird species."

That's because bird genomes, including the eight other (all extinct) moa species, have similar structures. That is, genes for particular traits tend to exist on the same chromosome and arranged relative to other genes in a similar way. The more clues to how to organize the $.25 of genome that a sequencer spits out, the better.

For the passenger pigeon, for instance, Shapiro and her paleogenomics team used the genome of the band-tailed pigeon to figure out how to organize their brusque Deoxyribonucleic acid sequences. She is trying to practise something like for the dodo, using the genome of the nicobar pigeon (the closest living species) as a template.

Information technology's "extremely difficult" to get genome organization right, said Charlie Feigin, a postdoctoral boyfriend at Princeton Academy who led the sequencing of the Tasmanian tiger genome. "Yous can look at closely related species for clues," just with no guarantee of getting the extinct genome bundled correctly. "That structure does thing, just the extent to which it has to be perfect [for de-extinction to succeed] is debated."

For the mammoth project, for instance, scientists are sequencing elephant chromosomes to get a better sense of how mammoth Deoxyribonucleic acid is organized, said Harvard's George Church, who is leading that projection. They're too hoping to better on nature, genetically engineering science resistance to the herpes virus into the mammoth genome (the ameliorate to keep information technology alive should de-extinction work). Some scientists believe that herpes infections helped kill off the mammoth. Church building said his lab aims to announce progress on both fronts this yr.

The best approximate is that, if scientists resurrected an extinct species by putting its reassembled genome into the egg of a living species, it would likely non exist a perfect replica of the original. A "de-extinct" passenger dove might eat what the original did but have different reproductive and social behaviors, for instance.

The putting-into-an-egg stride turns out to be harder in birds than mammals. A reconstructed genome can exist introduced into a mammalian egg with the cloning technique that produced Dolly the sheep. Only that doesn't piece of work in birds—"at least so far," said Brand. One hope is to get a workaround that recently succeeded in chickens, basically putting the genome into embryo cells that become eggs or sperm, to succeed in wild birds.

That's "one of the things Revive and Restore is focused on now," Brand said. "De-extinction is coming, gradually and certainly. It will eventually exist seen equally merely another course of reintroduction," similar bringing "wolves back to Yellowstone Park [and] beavers dorsum to Sweden and Scotland."

Republished with permission from STAT. This commodity originally appeared on Feb 27, 2018

Source: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/scientists-have-reconstructed-the-genome-of-a-bird-extinct-for-700-years/

0 Response to "How Do Scientists Read Dna So They Know We May Have Come Close to Extinction?"

Post a Comment